Somewhere in a time after Jimmy Rogers but just before Hank Williams, after the Carter Family but before Johnny Cash, back in a day that included Blind Lemon Jefferson, the Sons of the Pioneers, Glenn Miller, Ma Rainey, Benny Goodman, Xavier Cugat, Charlie Patton, Carmen Miranda and Spike Jones--Bob Wills swings on a musical star that shines over Texas and Oklahoma.

It was the era of the singing cowboy, with future millionaires Roy Rogers and Gene Autry staking their claims via movies, records, and radio appearances. Wills was definitely Western, but never pretended to be a saddle bum. He was a focused, energetic bandleader of the first order. His music was more at home on the dance floor than on any range.

A cigar-chomping, foot-stomping fiddler from deep in the heart of Texas, Bob Wills did things with Western music that simply had not even been thought of before. In his process of reimagining and distilling multiple genres into a musical creation intended to bring pure joy, he developed his own brand of Western swing.

James Robert Wills was born March 6, 1905, near Kosse in Limestone County, Texas. The first of ten children, Jim Rob learned to fiddle from his father, John, who had learned the tricky instrument from his father years before. Fiddles, called “the devil's instruments” because they made folks want to shake a leg, were frowned upon in the Bible Belt. The music income wasn’t steady, so Papa John supplemented the budget working as an itinerant cotton picker.

Living in dusty migrant camps scattered across Texas, young Wills soaked up a wealth of ethnic musical culture, from lonesome cowboy paeans to Mexican fiesta frolics; from Hawaiian war chants he heard on the radio to the Delta blues for which you would sell your soul. One of his favorite anecdotes was his tale of being teen Bob riding 50 miles on horseback to Childress, Texas, to hear Bessie Smith sing. Remembered Wills, “She was the greatest thing I ever heard.”

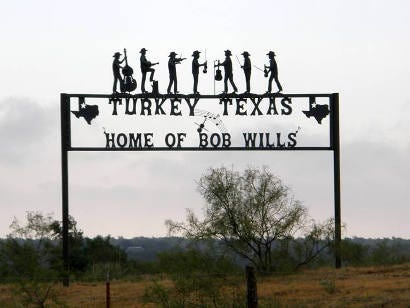

Wills first played the mandolin because his father needed a backup. Jim Rob was forced to change instruments, however, at a barn dance in Turkey, Texas, in 1915. His father lost track of time at the corn liquor wagon while his ten-year-old son paced nervously inside the hall. When the crowd rumblings began to sound like a great empty stomach, little Jim Rob picked up his father’s fiddle and “preached his first sermon.” John finally made it inside where the crowd had gone hog wild. He was astounded and proud.

Young Wills played with the family and other bands at dances and on hometown radio stations throughout the southwest. He hopped a freight out of Turkey at 16 and landed in New Mexico. The 1920s were allegedly roaring, but Wills spent his late teens bumming around in odd jobs and finding live music wherever it might be played.

By his early twenties he was married to his first wife. “He was always happier when he was married,” quipped a band member in later years. Wills worked as a barber or as a touring musician in minstrel and medicine shows. One such show had too many Jims, so he formalized his first name as Bob.

During the summer of 1929 in Fort Worth, Texas, he and guitarist Herman Arnspiger formed the Wills Fiddle Band. A year later the Depression had hit hard, but music was working out for them. They were joined by the singing cigar salesman Milton Brown. The trio began performing in turbans over KFJZ (Fort Worth Jazz) as the Aladdin Laddies on a program sponsored by Aladdin Lamps.

The Laddies went statewide over the Texas Quality Network originating from WBAP (We Bring A Program), also in Fort Worth. The Burris Mill and Elevator Company, makers of Light Crust Flour, picked up the sponsorship and on New Year’s Day, 1931, the Light Crust Doughboys made their debut. Country music historians point to that date as the birthday of Western swing. The catchy new sound had blossomed like a wildwood flower. It carried a Western familiarity with hillbilly echoes, but it was lively and quick.

The Doughboys cut their first records for the Victor label the following year, but all was not well. W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel of the Burris Company was not on board with the yee-ha antics of Big Bob and his diehard fans. He wanted the show that carried his name to appeal to Granny serving fresh biscuits and homemade strawberry preserves in her family kitchen. Not to a bunch of wild-ass shit-kicking bull riders who drunkenly danced until the sun came up over the prairie. Wherever and whenever Wills and his band played, there was booze, there was carousing, there were fights, there was lust, there were boots scooting.

Not only was Pappy displeased by the kind of country trash Wills attracted, he wasn’t at all convinced this rocking band of electrified hillbillies were pulling their own weight. He paid the boys $7.50 a week but for a big salary like that, they had to work shifts at the flour plant. When Wills complained that his talents were being wasted driving a truck, O’Daniels conceded, but still made the Doughboys stay at the plant 8-hours a day rehearsing.

Despite the popularity of the prison tune “Twenty-One Years” and the “Chicken Reel,” Pappy cut the cord in the hot August of 1933. Wills was unemployed, and hard times or not, he rejoiced in his liberation from the biscuit king. On his way out the door he lassoed vocalist Tommy Duncan as well as the banjo demon Johnnie Lee Wills. The new incarnation would be called Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys. His group might include anywhere from six to twenty-three players, and every one played as clean as country water.

First stop was a trip up north along the Chisolm Trail from Fort Worth to Oklahoma City for an on-air gig at WKY radio. Before Wills could light his first Roi-Tan cigar, the vindictive O’Daniel bought up all the commercial time and the Playboys had to pack up their gear and hit the highway.

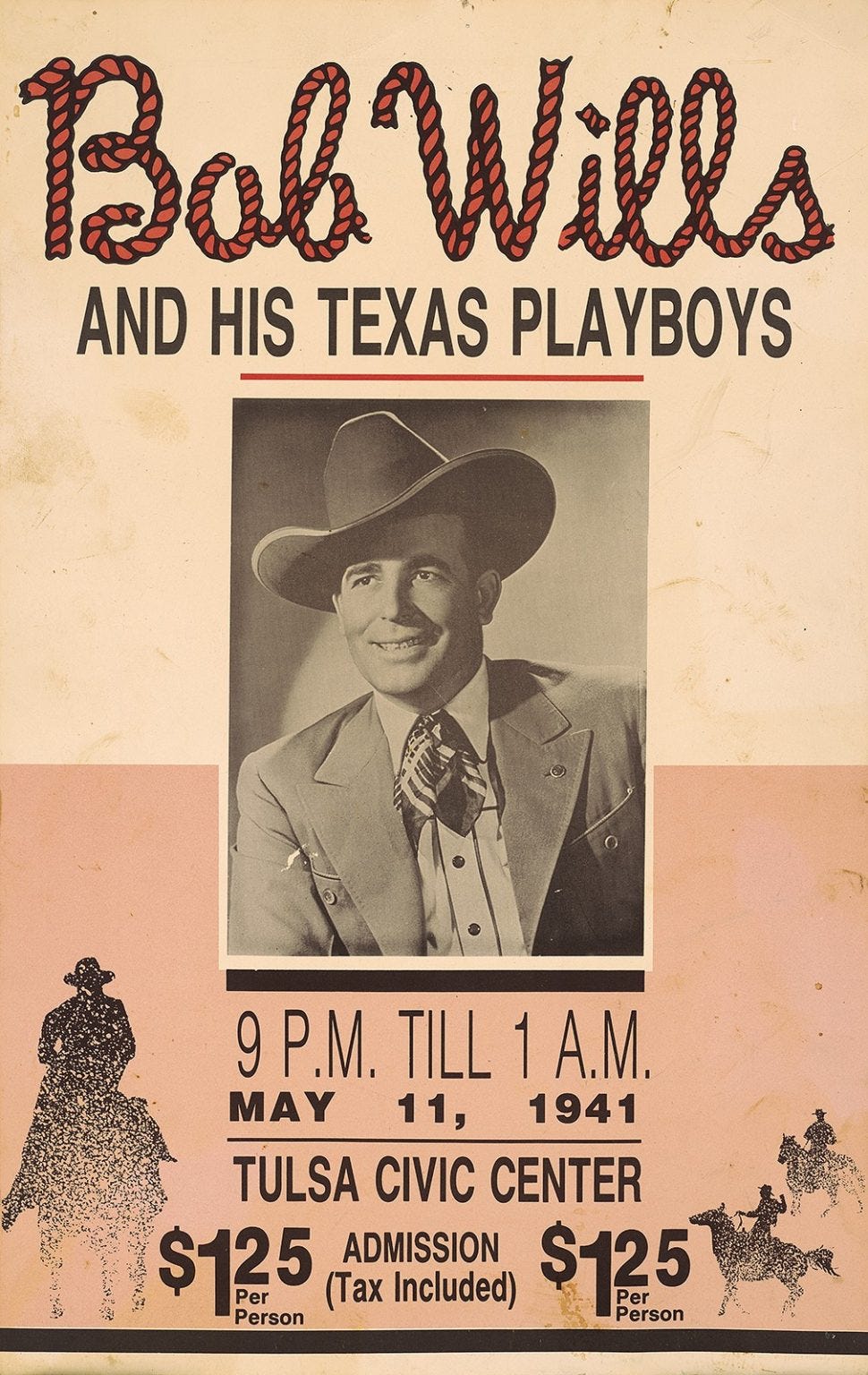

As the bus took them back to Tulsa, the feud subsided.1 Wills struck up a relationship with KVOO (Voice Of Oklahoma) that would last for 24 years. A powerful 50,000 watt signal carried the daily noon broadcast from Cain’s Ballroom to the homes, farms, and ranches across Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, and Missouri.

Swing was the big band rage of the day. Wills was doing the same with country, adding drums, much to the chagrin of the Grand Ole Opry, and a full brass section. Combined with traditional instruments including rinky-tink piano and a wailing steel guitar that could cry or take to the highway, Western music had a new jump that fit the times.

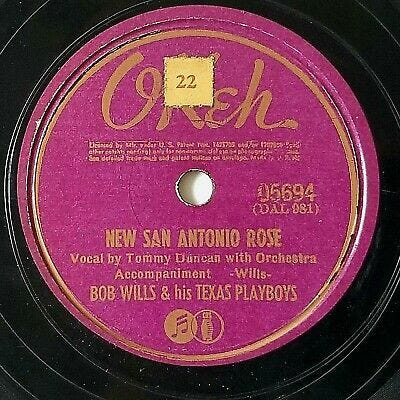

At the center of it all was Wills himself, dressed in sharp suits, then as the reputations grew, the high rhinestone cowboy fashions of WWII Western stars. When he wasn’t playing, Wills hustled. His band recorded for a number of labels including Okeh, Vocalion, Decca, Columbia, and MGM labels.

Bob’s Wedding Bells. Edna Posey, married 1926, divorced 1935, daughter: Robbie Joe Wills Ruth McMaster, married 1936, divorced 1936 Mary Helen Brown, married 1938, divorced 1938, remarried 1938, divorced 1939 Mary Louise Parker, married 1939, divorced 1939, daughter Rosetta Wills Betty Lou Anderson, married 1942, four children: James Robert II, Carolyn, Diane, and Cindy Wills

People could take the recordings home, but seeing Bob cooking live was unforgettable. He pranced and strutted, calling out to his musicians, conducting with his bow, urging his spotlight performers with falsetto shouts of encouragement, carried away and wild-eyed. “AHH-Hah!” All that in the midst of ten or twelve thousand people who had driven from miles around to experience the ultimate of Saturday nights. Bob Wills was something else.

The hottest band west of the Rio Grande reached its zenith as war clouds gathered in 1940. That year Wills and the Playboys released a vocal version of their signature song that they had been playing instrumentally for two years. “The New San Antonio Rose,'' recorded for the Okeh label on Apr 16, 1940 featured the vocals of Tommy Duncan. Record stores couldn't keep it on the shelves. It became the first Playboys million seller.2

World War II would have the same effect on Western Swing as it did for the big bands. One by one the Playboys went off to war. Wills was ready to fight, ready to take his mojo to the front. In 1942, at 38, he enlisted only to be released from active duty with a medical discharge in July, 1943.

The bandleader relocated the boys to Hollywood, where they appeared in 19 motion pictures like Saddles and Sagebrush (1943), Wyoming Hurricane (1944) and Rhythm Round-Up (1945). They also performed another live noon radio show, this time on KMTR (which later became KLAC Los Angeles, California), as well as a series of gigs at San Diego’s Mission Beach Ballroom. In Jan, 1944, Billboard reported the band’s concerts at Oakland’s Civic Auditorium “out-grossed Harry James, Benny Goodman, both Dorseys, et al.”

With homes in Santa Monica and Fresno, Wills opened his own nightclub, “Wills Point” in Sacramento, and was heard in that city over KFBK. The Playboys also recorded over 400 songs for syndication on KGO (General Electric Oakland.) These recordings 1946-47 were believed lost until they weren’t anymore, and are now available on boxed sets released in 2014 and 2021.

After two monster hits in 1950, “Faded Love” and “Ida Red Likes the Boogie,” the fever pitch of it all began to fade. By mid-decade, with Elvis and the hybrid which Wills helped create, namely rock and roll, the change was obvious. And, as the heyday sank slowly in the West, so eventually did the bandleader’s health. Wills suffered his first heart attack in 1962 and another the following year that forced the first breakup of the band.

In 1968 Wills was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. Texas honored him with a special day on May 30, 1969. The very next day he was paralyzed by a severe stroke and confined to a wheelchair.

In 1973, Wills picked a roster of Playboy all-stars, and with superstar Merle Haggard, mapped out plans for a multi-disc package called For the First Time. Wills was well enough to participate in some Texas Playboy reunions. On the first day of the first recording session with Haggard, Dec 3, 1973, Wills had another stroke and never regained consciousness. The album was recorded as scheduled, and sold well.

Seventeen months later, on May 13, 1975, Wills died of pneumonia in a Fort Worth rest home. The Playboys reformed under Leon McAuliffe and Leon Rausch, and in 1977 were named the Country Music Association’s instrumental group of the year. Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys were inducted under the category “Early Influence” into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999. He was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007.

Today Bob Wills has transcended into legend. Revivals are as common as Texas fleas. Cool before country was cool, Wills brought powerful change and undeniable class and vigor to a music that had once been referred to as hillbilly. Western swing was the word, Bob Wills was the prophet. And it was very good.

Bob Wills is still the king.

Pappy stayed in Texas where he organized his own band and eventually got elected the longhorn governor, then senator. Charles Durning plays a factionalized version of O’Daniel in O Brother, Where Art Thou (2000).

Made me want to go back in time and see these bands live

Thank you! That story wrote itself!🐄