In one of the earliest examples of modern film making, actor Justus D. Barnes aims his Colt 1878 Double Action revolver pistol directly into the camera and fires. It is 1903, so early in cinematic history that there is no Hollywood and the term “director” hasn’t been coined. As far as movie history is concerned, it is the equivalent of a cave drawing. Instead of spears being used on mammoths, guns are the weapons of choice, silently exploding in almost every one of the film’s dozen minutes.

Early audiences were horrified by the scene. Think about it. Few who had ever seen a gun fired at them so close and deliberately were around to tell about it.

Scene 14 - Realism. A life size picture of Barnes, leader of the outlaw band, taking aim and firing point blank at each individual in the audience. (This effect is gained by foreshortening in making the picture.) The resulting excitement is great. This section of the scene can be used either to begin the subject or to end it, as the operator may choose. The End. Sold in one length only, 740 feet. Class A. Price 111.00. CREATED/PUBLISHED United States : Edison Manufacturing Co. 1903.

Wherever the shocking gunfire was placed, according to John Tuska in The Filming of the West, “women screamed or fainted away; men were terrified or fell to marvelling.” After the stunning sequence, audiences bonded in relief, then more often than not joined in cathartic cheers and demanded the film be screened a second time. The overwhelming enthusiasm made the producers of brief arcade novelties take notice. In a few cranks of the Edison Kinetograph the game changed from curiosity to art form.

Almost overnight, it was realized that films with storylines would sell more tickets. That meant authenticity everywhere, especially in the action and the peril. If the script called for gunfire, it had to appear to be the real thing, regardless of the dangers involved on the set.

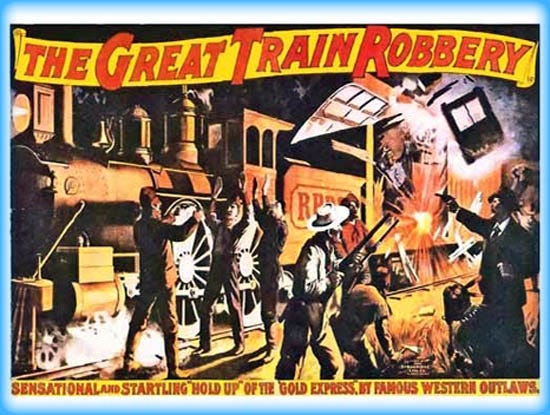

Often cited as the first western--even as the first motion picture--The Great Train Robbery (1903) was actually neither. Brief movement studies such as The Sneeze (1894) and The Kiss (1896) had come before. Cripple Creek Bar-Room Scene (1899), a four-minute plotless Edison tableau is now considered to be the first motion picture with a western theme.

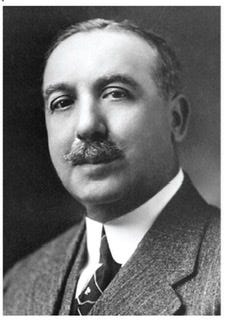

Credit the evolution to Edwin Stanton Porter, born in 1870 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania. Porter’s start came with a projectionist job, operating an Edison’s Vitascope for astounded New Yorkers in 1896. After touring with the contraption across South America and the West Indies, Porter came home to work at Edison’s East Twenty-third Street studio in Manhattan. Quickly he advanced from cameraman to head of production.

His The Life of an American Fireman (1902), portraying a firefighter at home and on the job, required an incredible 500 feet of film, ten times the standard necessary for standard productions. The rescue of a child from a towering inferno electrified his audiences. Porter suspected he was on to something.

“Encouraged by the success of this experiment, we devoted all our resources to the production of stories, instead of disconnected and unrelated scenes.”--Edwin S. Porter

In September 1903, Porter was commissioned to produce a promotional film for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in New Jersey. The film would show railroad cars so clean that heroine “Phoebe Snow” could travel in elegance without soiling her whitest ruffles. During the shoot, Porter established a rapport with railroad officials.

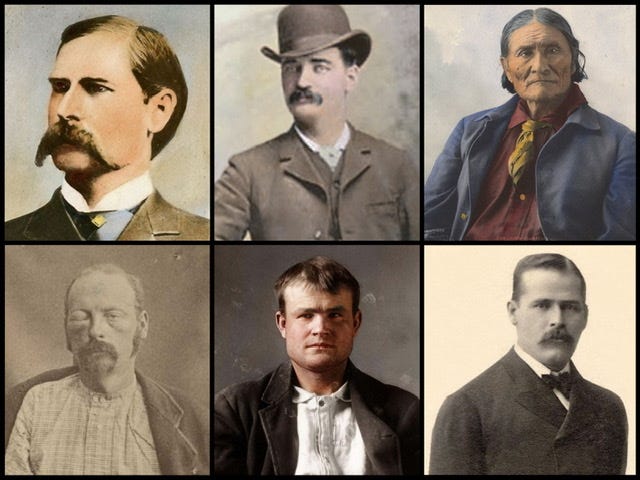

In 1903, the Old West was a current event. Bat Materson was a New York City sports writer who specialized in boxing. Wyatt Earp had hung up his Buntline special to prospect in Colorado. The celebrated Apache leader Geronimo was a prisoner of war in Oklahoma. A-list outlaw Cole Younger, fresh from a 25-year prison sentence, was out preaching the evils of crime. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were robbing Argentine banks.

The exploits of those two along with the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, also known as “The Wild Bunch,” were the inspiration for Porter’s story. He quickly jotted the script on a legal pad, then raised the $150 shooting budget, roughly $4,600 in 2021 dollars.

Vaudevillian George Barnes was hired away from Huber’s Museum to play a thief. Frank Hanaway was chosen for riding skills gained while serving with the U.S. Cavalry. Marie Murray, fresh from her triumph as Phoebe Snow, would be in the dance hall scene. A 21-year-old salesman, Max Aronson was hired as a rider for 50 cents an hour although he did not know how to ride.

Shooting began at a livery stable in the countryside around wild West Orange, New Jersey. The director and his cast then galloped to an Essex County park. When they arrived, Porter noticed that Aronson was missing.

The next day, Aronson made it to the set but had difficulty remaining in the saddle. Rather than fire him, Porter thought such dramatic tumbles might be crowd pleasers. Aronson also filled the role of a panicky passenger who is shot while attempting to run away.

Near Paterson, New Jersey, the first fight scene atop a moving train was filmed. Just before the train reached the Passaic river bridge, a dummy was tossed from the coal car and landed on a trolley track below. The train’s engineer pulled the emergency brake. Passengers believed they had witnessed a real death. When the stuffed stuntman was revealed, tempers flared. Porter was overjoyed that his stunt looked so real.

The fourteen scenes in the finished product were action-packed. Desperados held up a telegraph office, hog-tied the operator and forced the train to make an unscheduled stop. Passengers were marched outside at gunpoint. One of them (played by resident dude Aronson) was shot dead in his tracks when he tried to run away. A strongbox was blasted, the mail car was relieved of money bags. The outlaws made tracks, even though one of them had just played the passenger shot in the back. Aronson kept falling off his horse.

Meanwhile, back at the telegraph office, the operator’s daughter discovered her father and set him free. He warned the townspeople at a dance hall, where a group of hooligans have been amusing themselves by firing at the feet of a “tenderfoot” to make him “dance.” (A first time for that Western movie gimmick also.) And yes the dancer was also the versatile Aronson resurrected from the train station. A posse formed, a dizzying chase ensued, and the bandits were cornered in a wooded area and gunned down.

“SENSATIONAL AND STARTLING HOLD UP OF THE ‘GOLD EXPRESS’ BY FAMOUS WESTERN OUTLAWS.” -Edison advertising poster

Porter, an absolute original (as a 33-year-old director had given us the term “shot” for what they were doing with movie cameras) never again showed similar genius. His followup The Great Bank Robbery (1904) was a dud, then he hit total bottom with The Little Train Robbery (1905) wherein naughty children hijacked a toy train. One critic noted that when he directed Mary Pickford in Tess of the Storm of Country (1908), “his technique hadn’t progressed one iota.” After leaving Edison in 1909, Porter formed two film companies before retiring from production in 1915. He died in 1941.

As for Aronson, his eyes had been opened to new career possibilities. He changed his last name to Anderson, headed West, and finally learned to ride a horse in Hastings, Nebraska. After persuading a Chicago producer that westerns should be staged on location, he shot a 1909 film in Golden, Colorado. In 1910 in Oakland, California, he changed his name to Broncho Billy Anderson, and went on to fame as the movie’s first cowboy star in over 375 westerns over the next seven years.

During an autumn romp 118 Novembers ago in the New Jersey woods, the movies and westerns were changed forever. The cinematic story began to take shape. The Great Train Robbery not only defined a genre, it laid the very foundation for the future of screen entertainment, guns and all.

And what about those firearms? Had Justus Barnes fired real bullets at the camera? Short answer: of course. The blanks that would have fit that particular pistol had yet to be invented.

“Every time a gun is used, it is pointed away from the person/camera. This was done for two reasons. The first being that film was in its early stages, so they didn’t think the audience could see the tilted guns. The second reason is that blank cartridges for pistols weren’t invented/widely used at the time, so they used real bullets.” --IMDB

Even in the barroom dance scene, the tough guys were firing real rounds near the future Broncho Billy’s boots. When Barnes filmed his famous scene, he was instructed to shoot around the camera as soon as the operator stepped away so that Mr. Edison would not have to provide another piece of equipment.1

The original negative of The Great Train Robbery resides in the Library of Congress and fresh prints can be made from it. Many copies contain sounds and music that were added after the fact. This copy has no sound, but some excellent hand tinted frames.

Final footnote. Incredibly, on set injuries for The Great Train Robbery were limited to scrapes and bumps. The first recorded deaths on a movie set were actress Grace McHugh and camera operator Owen Carter who drowned in the Arkansas River while filming Across the Border (1914) near Canon City, Colorado. The first gun death came on the set of The Captive (1915). Live ammunition was used by soldiers attempting to break down a locked door. For the next scene, after the door is down, director Cecil B. DeMille ordered the extras to reload with blanks. One inadvertently left a live round in his rifle. Another extra, Charles Chandler, was killed instantly when he was shot in the head.

A shorter version of this story originally appeared in The Old West: Day by Day published by Facts on File, New York, New York, ⓒ 1995 Mike Flanagan