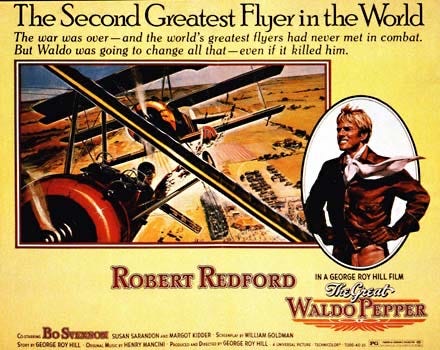

The Great Waldo Pepper, George Roy Hill’s 1975 homage to the barnstormers of the Soaring Twenties, opens with a shot of an aging photo album. Names and faces of great stunt flyers pass silently, sealed with the glue of forgotten heroics. Today that film is regarded as one of the last to include 100% true stunts. Two years after its release, George Lucas unveiled Star Wars, and ever since computer graphics have been going where no pilot has ever gone.

We regard those early pilots with awe and respect. They learned fast or not at all; they knew their machines as most people know their hands. Realistically they were aware of what could happen at any moment, they just put a lot of faith in luck. Like the tightrope walker or the Niagara Falls barrel devil, they were able to shelve those fears for the thrill of attempting something impossible—all the while with the cameras rolling.

The lure of film, with its abilities to capture death-defying stunts for all time and pay for the privilege, made it even more worthwhile. The art of flying, the magic of cinema--it was a match made at 5,000 feet when the Wild Blue Yonder hit the Silver Screen.

Film came just before airplanes. Thomas Edison was hand-cranking celluloid sneezes and prizefights while the Wright Brothers were calculating the wind beneath their wings. The first leaps at Kitty Hawk took place in 1903, the same year the first movie with a plot, The Great Train Robbery, hit the theatres. The Library of Congress owns the earliest known film of a plane in flight: “Ludlow’s Aerodrome” from 1905.

From there, the dates intermingle. Motion picture companies set up business in Los Angeles in 1907; international air meets began at Dominguez Ranch south of the city soon after. Wilbur Wright carried the first airborne cinematographer in his Flier over Italy and France in 1908.

Actress Mabel Normand took to the air with an uncredited pilot in a Wright Model B in “A Dash Through the Clouds” in 1912. Full movie click here.

Most of the flying done in the Jurassic era of filmdom had little to do with stunts. Moviegoers were thrilled enough to witness planes take off, soar, and land. The idea to get crazy up there came out of World War I, when the airplane was first used as a weapon of war.

While early newsreel photographers filmed bloody combat over Europe, the idea of using air stunts to further plotlines was catching on in Hollywood. Charles Gaemon became the first person to jump from a plane to a train in Out of the Air, released in 1915.

On March 16, 1915 studio chief Carl Laemmle orchestrated a major public event to launch what the Times hailed as “the greatest motion picture city in the world,” on 235 San Fernando Valley acres. For the Universal City opening, Hoosier pilot Frank Stites, 33, was hired to recreate a stunt that had been cut from D. W. Griffith’s Hearts of the World.

What should have happened: High above the crowd, a pilotless dummy airplane loaded with explosives would “fly” from one end of a long cable to another. At about the halfway point, Stites would swoop down and drop a fake bomb into the prop plane. The explosives would go off, Stites would take a victory lap, then land and be greeted by the crowd.

Jessie Maude Nelson, Frank’s wife of eight years, kissed him goodbye and it really was goodbye. She faded into the crowd of 500 Angelinos to witness her high-flying Hollywood stuntman do his thing. Right on cue, Stites dive-bombed the dummy plane. About fifty feet above it, Stites got ready to drop the fake bomb. Suddenly his target exploded prematurely. The blast pressure caused Stites to lose control of his craft. Frank was either trying to parachute or he simply fell out of the cockpit. Regardless, the crowd watched in horror as the pilot fell 300 feet to his death.

Mrs. Stites told the press that her husband had a premonition after the loss of friend and pilot Lincoln Beachey, 28, who had met his fate two days before at a San Francisco air show. According to Nelson, a melancholy Stites shrugged over the newspaper story and said “I guess I’ll be the next one.”

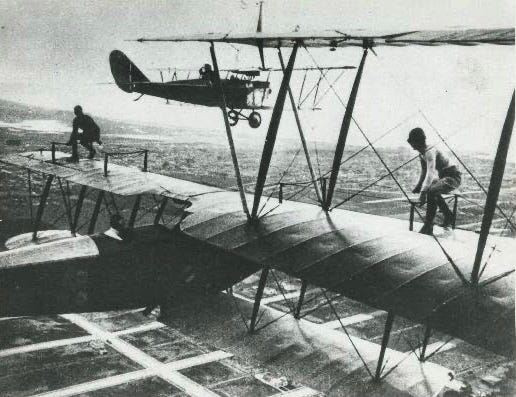

War pictures first appeared toward the end of the actual Great War. Newsreel-savvy audiences clamored for authenticity. Already the new breed of daredevil, the barnstormer, thrilled audiences across the country with feats of gravity-defying spins, close call dives, and borderline insane wing walking. Many of these pilots were fresh from the war. Others were starstruck kids, ready to risk it all for a fast buck and a shot at immortality.

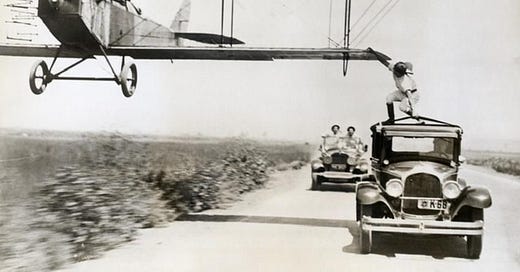

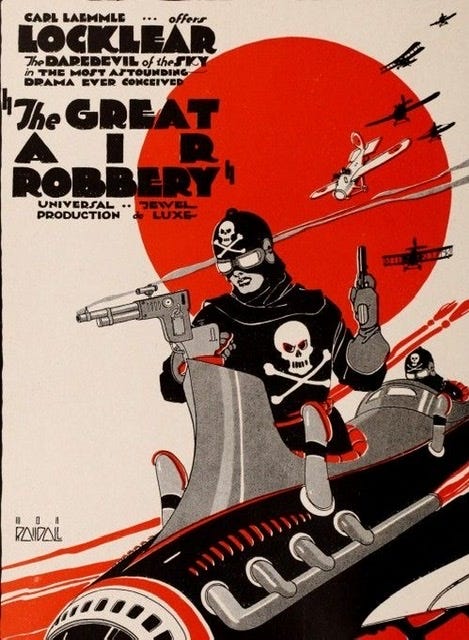

Al Wilson built his first airplane in his Ocean Park, California, backyard when he was 18. When he couldn’t get it to fly higher than 50 feet, he sold it to a production company to blow up. Following an instructing stint in Venice, Wilson flew a Bleriot monoplane in Cecil B. DeMille’s We Can’t Have Everything (1917). He went on to become one of Hollywood’s more successful stunt pilots in the 1920s, at times hanging from his ankles from one plane then dropping into one below. While Wilson and a dozen others made names for themselves in LA, rumors of a new sensation blew in from Texas.

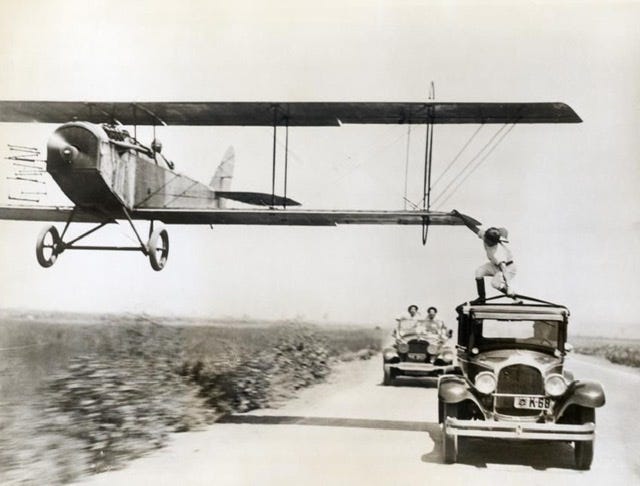

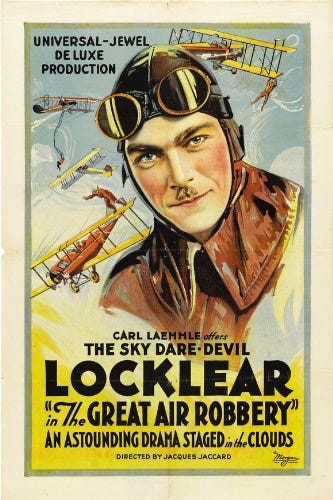

Writers of the day talk about Ormer Locklear as if he were Jesus in goggles. They said he looked like Clark Gable. Young, dashing and fearless, Locklear gained notoriety dancing across the wings of a Curtiss Jenny in his native Lone Star state, demonstrating to young Army Air recruits that army planes were safe, even for a walk in the clouds. On November 8, 1918, he jumped from the lower wing of one biplane to another at 5,000 feet, the first time anybody had done that.

Locklear’s daring was rivaled only by his imagination. Soon he was boarding planes in flight, climbing from racing automobiles on rope ladders. Another time he stepped from the top wing of one plane to another. The star of the Locklear Flying Circus earned $3,000 a day for his live shows.

"I don't do these things because I want to run the risk of being killed. I do it to demonstrate what can be done. Someday we will all be flying." --Ormer Locklear

The brief but soaring career of the star of The Great Air Robbery ended tragically at DeMille Field No. 2 the night of August 2, 1920. Locklear insisted on performing a spin straight down from 3,000 feet for a scene in The Skywayman, feeling a miniature would appear fake. Locklear initially protested that the whitewash on the Jenny added thirty pounds to the frame, then shrugged it off. A quick kiss from his girlfriend and he was situating himself into the rear cockpit behind pilot Skeets Elliott.

At the designated altitude they lit wing-mounted magnesium flares. Then Elliott maneuvered into a full dive toward ground zero. Whether their own tremendous light or the spotlights from below caused the disorientation is uncertain. The Jenny slammed full speed into the ground, exploding in flames in an oil sump at Third and Crescent. Both men died instantly. Locklear’s career, from his aerial show to his last movie stunt, lasted all of 16 months. He was 29.

Rather than discouraging prospective film flyers from fairly certain unhappy endings, Locklear’s death opened the floodgates. Stunt flyers became synonymous with their most dangerous feat. Maurice “Loop the Loop” Murphy performed his biggest loop from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

Frank Clarke, known for changing planes while locked in handcuffs, created a stir when he dismantled his Canadian Jenny, then reassembled it on top of the Los Angeles Railway Building. City officials believed it was only for photo purposes, but Clarke couldn’t resist the opportunity. On the night of December 14, 1920, he revved the engine and took off from the rooftop.

As the stunts grew more outlandish, Los Angeles County enacted a series of air traffic regulations in 1923. Leo Nomis was the first cited under the new ordinance when he flew too low over a Hollywood High School football game.

Then, as today, Hollywood realized how fast the future was approaching. The stunts of the early days would become tomorrow’s novelty. How many times could the good guy run up under a plane in a speedboat, climb into the cockpit, knock the bad guy off the wing, then bank into the sunset? The bar was about to be raised on film’s power to amaze.

About that time, producer Jesse Lasky was approached by John Monk Saunders, a World War I pilot who replaced dog fighting in France with screenwriting in LA. Wings went into production with director William Wellman, who had himself flown with the Lafayette Escadrille and been shot down in the war. The astronomically budgeted $2 million picture would star Buddy Rogers, Richard Arlen, Clara Bow, and newcomer Gary Cooper.

You don’t see the Alamo in the final cut, although most of the exteriors for Wings were filmed around San Antonio, Texas, during the summer of 1926. Nearby Fort Sam Houston provided 3,500 infantrymen as extras. Some 300 pilots flew 200 WWI vintage fighter planes, including Fokkers and Spads. Wings assumed a lofty position in cinema history as the last of the silent blockbusters and the first Academy Award® Best Picture winner.

Among the impressed was aviation pioneer Howard Hughes, who responded with a four million dollar picture, Hell’s Angels. Newspapers chronicled the filming with lurid tales of close calls and near disasters filling the daily rushes. Seventy stunt pilots were on payroll, including Al Wilson and the first woman to perform aerial movie stunts, Pancho Barnes (1901-1975).

Barnes (born Florence Leontine Lowe) wrote a larger than life chapter in aviation. One of the first female pilots licensed in the U.S., she would become Lockheed’s first female test pilot. After surviving a crash during the 1929 Women’s Air Derby, she returned the following year to claim the world women’s air speed record, breaking Amelia Earhart’s record with a speed of 196.19 miles per hour on Aug 4, 1930. Barnes originated the Rancho Oro Verde Fly-Inn Dude Ranch, affectionately known as the “Happy Bottom Riding Club'' near Edwards Air Force Base in California. It became a favorite hangout for test pilots fresh from the hangar and movie stars alike (1935-1953) and was memorialized in The Right Stuff (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979) by Tom Wolfe.

Just over a year after Hell’s Angels premiered, on September 29, 1931, Hollywood’s top twenty stunt pilots formed the Motion Picture Pilots union, affiliated with the AFL. It would be the first but not the last organization formed to secure safety standards for an increasingly risky occupation.

So often the triumphs were tempered by tragedy. Leo Nomis flew in a string of hit pictures including Birth of Nation (1915), The Dawn Patrol (1930), and The Lost Squadron (1932). He was killed in 1932 while flying for Sky Bride. Harry Crandall, also a Hell’s Angels pilot, died while flying mail from Burbank to San Francisco. Roy Wilson was killed that same year, on the set of War Correspondent, spiraling down from 3,000 feet in a Speedwing Travelair. Al Wilson succumbed to injuries suffered at the National Air Races in Cleveland when he crashed near the grandstand.

Air battles of World War I remained hot movie properties throughout the Depression, in films like Ace of Aces (1931), The Eagle and the Hawk (1933), and two versions of The Dawn Patrol (1930 & 1938). Airplanes figured prominently into stories of dope smuggling, as in Parachute Jumper (1932).

Biplane iconically dislodged a Skull Island’s greatest gorilla from the Empire State Building in King Kong (1933). BTW, Fay Wray was married to John Monk Saunders of Wings fame.

The eras officially changed with the onset of World War II, and so did movie stunt flying. Stock footage of real battle sequences appeared in almost all the war films that were produced during and after the war. By the time of Twelve O’Clock High (1949), there were miles of combat footage, along with plenty of B-17s to fly.

Stunt flying nostalgia looped full circle in the 60s and 70s. Pilots with the Wright stuff were fondly remembered in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, or: How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours and 11 Minutes (1965). Director Ken Annakin recreated several flyweight machines from original blueprints, including a Phoenix Flyer and a Passat ornithopter.

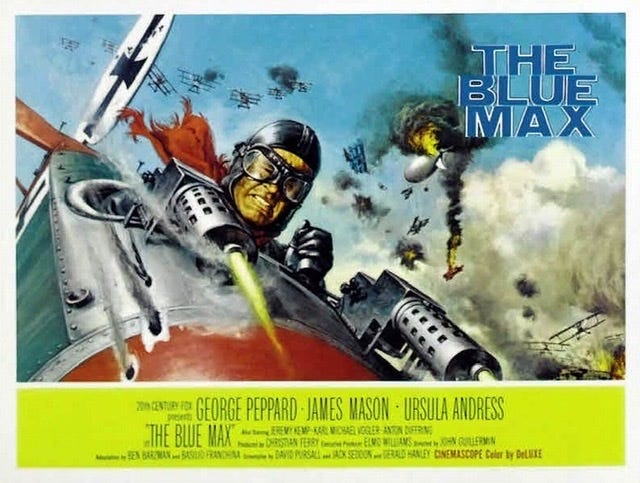

Something the audience hadn’t experienced in years, a World War I dogfight spectacular, came the next year with George Peppard starring as Bruno Stachel in The Blue Max (1966). The smug young member of the German fighter squadron flies in hot pursuit of 20 kills. Two Fokker Dr.1 Triplanes were built in Germany for the film, complimented by three Fokker D-VIIs, assembled in France. Shot over Ireland, Newsweek raved, “stunt flying so good as to be almost unbearable.”

In 1975 director George Roy Hill, fresh from The Sting and a pilot himself since age 17, embarked on the epic barnstorming flick, The Great Waldo Pepper, starring Robert Redford. Frank Tallman coordinated the stunts and did much of the flying. One of the film’s stunts called for Pepper’s plane to swoop down the main street of a small town. Power lines were moved underground at Elgin, Texas, making way for the pass by Tallman’s Standard J-1. Tallman pulled on a rubber Redford mask for the piloting sequences. Redford did his own wing walking.

When Waldo Pepper wrapped (no fatalities, but a month in the hospital for Tallman after he went through some power lines) so too did an era in Hollywood stunt flying. Airplanes would never fly out of the movies altogether, but things would be different in films like Top Gun (1986), Air Force One (1997),and ConAir (1997). As an example of how fast and how quickly things changed, three real Mitsubishi A6M Zeroes became an invading force of 350, thanks to CGI, in Pearl Harbor (2001).

Director Martin Scorcese took to the skies for the Howard Hughes biography The Aviator (2004). Cinematographer Robert Richardson had to film Leonardo DiCaprio taking an experimental XF-11 into a fiery crash in Beverly Hills. Retired American Airline mechanics Barney Peterson, 78, and Jack Kearbey, 73, provided airplanes for the film, handcrafted World War I fighters built from the original blueprints. Their actual size planes were used for taxiing segments, but takeoffs, in-flight sequences, and landings were used using one-fifth scale models.

As technology changed, so too did the either/or life and death world of the stunt pilots. Modern movie stunt personnel maintain the same rigid code set by their predecessors. They will do the stunt no matter how dangerous, they will make it look great on film, and if it doesn’t they will go back and do it again and again. Male and female stunt professionals are still as tough and courageous as ever.

No wonder nostalgia reigns anytime you see a leather-helmeted flyer pop on the goggles and hop into the cockpit, ready to risk his or her scarf-wrapped necks. Their legacy was simple. What they did had to be seen, had to look good, and had to be real. The rest could be left to movie magic.