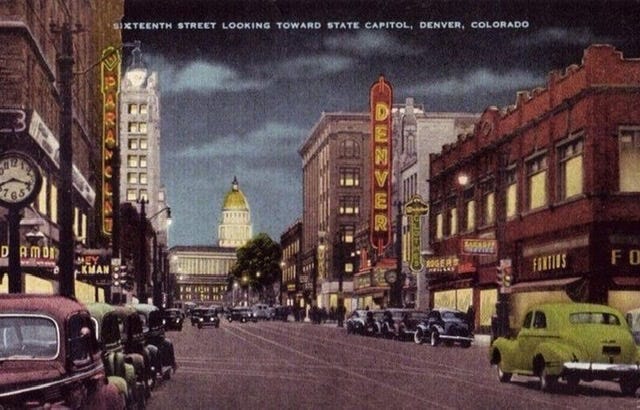

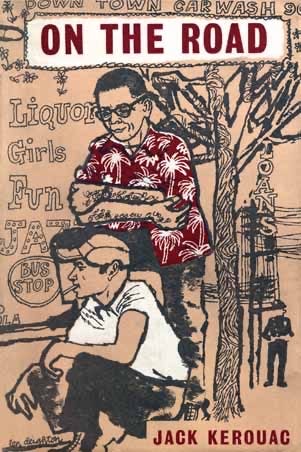

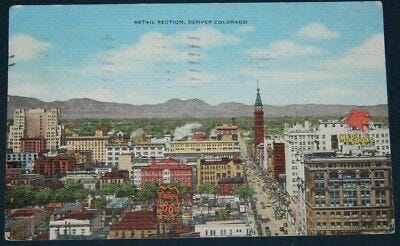

“I walked around the sad honky-tonks of Curtis Street; young kids in jeans and red shirts; peanut shells, movie marquees, shooting parlors. Beyond the glittering Street was darkness, and beyond the darkness the West.”

– – Jack Kerouac from On the Road

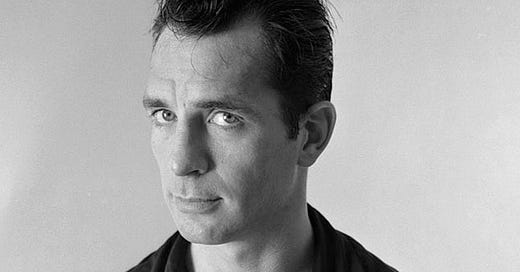

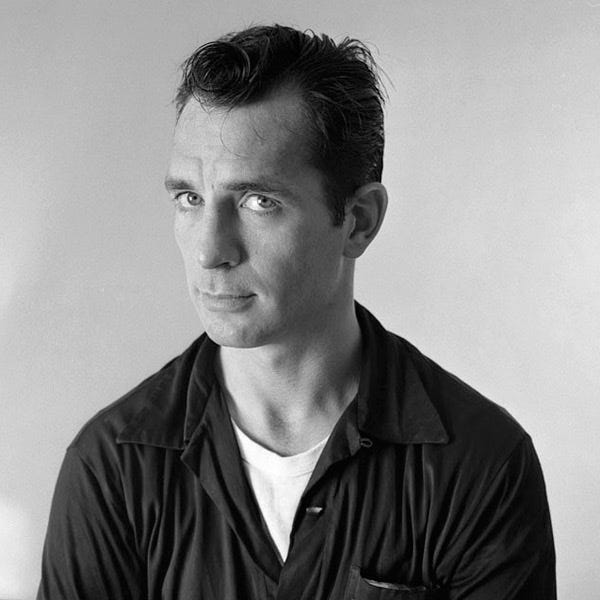

Before Massachusetts-born Jack Kerouac, visiting writers had mostly painted Denver in travel-brochure terms, hailing the clean air, the unspoiled scenery, and the vibrant community. As the writer transformed himself from invisible observer to the revered chronicler of the postwar “beat generation,” it was clear the city had implanted itself as a character in his prose.

More than a backdrop, Kerouac saw Denver as the ultimate destination for his desolation angels, an urban reality complete with a raucous nightlife. It was the perfect home for skid row poets, definers of decay, and the outlaw aesthetic of broken dreams and fresh starts.

“Jack Kerouac is accused of writing about people going nowhere,’ moaned an early critic, “ but they were always going to Denver and that is a definite destination indeed.’ Kerouac first saw Denver as the high point of his 26th summer. That untethered rub of being broke, drunk, and hungry but still hovering effortlessly a whole mile above the shorelines of his childhood, turned the key that unlocked the inner music. That wild bongo beat inner-rhythm that at once helped him understand everything and nothing at all stayed with him for the rest of his life.

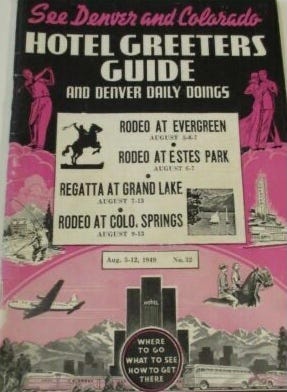

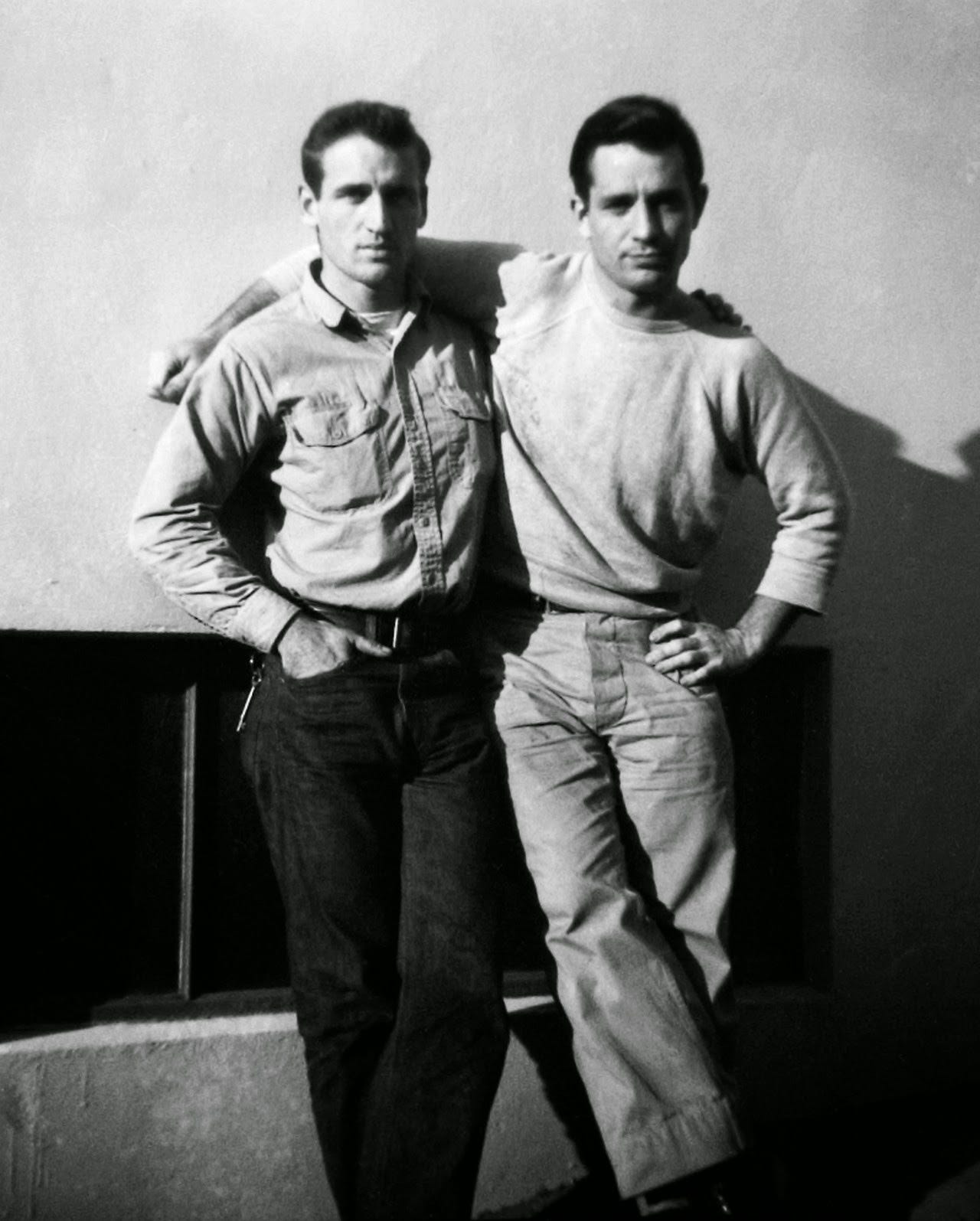

“He let me off on Larimer Street,” says Sal Paradise, Kerouac’s impressionable drifter persona in On the Road. “I stumbled along with the most wicked grin of joy in the world, among the old bums and beat cowboys of Larimer Street.” It was July of 1947. Kerouac had bused and thumbed his way out west to find poolhall prodigy Neal Cassady, his soul advocate whom he would enshrine as Dean Moriarty in On the Road.

Cassady was raised on Denver’s mean streets and had grown up tough, wise, and crazy. His passion was stealing cars, racing them through the foothills to the west, and eventually abandoning them on mountain dirt roads or in high altitude towns like Black Hawk and Central City. By his own estimate he anonymously borrowed some 500 vehicles between 1940 and 1944. Police apprehended him just three times.

When the nomadic Kerouac appeared on the Queen City scene, Neal was flopped in a six-dollar-a-week basement room. From those humble surroundings Cassady attempted a postwar balancing act. He maintained a complicated relationship with his wife Luanne that included University of Denver coed Carolyn Robinson on the side. Those two shared an already full Cassady plate with a young unknown poet from Columbia University named Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac would view his friend’s confusing sexual slapstick as human comedy in On the Road. His publishers insisted he give them all fake names.

Denver could still be “Denver.”

Other local figures with active roles in the social whirlwind would be brother and sister Robert and Beverly Burford who appear as Ray and Babe Rawlins (‘a tennis-playing surf riding doll of the West”), and Edward White whom Kerouac had met when White was at Columbia studying architecture. White was the one who suggested that Kerouac `”sketch” his scenes and characters as a street artist might his curious subjects.

To Kerouac it was a bit of a literary overhaul. Any character, all emotions, everything could be captured but never tamed in furious speed raps ricocheting in all directions at once.

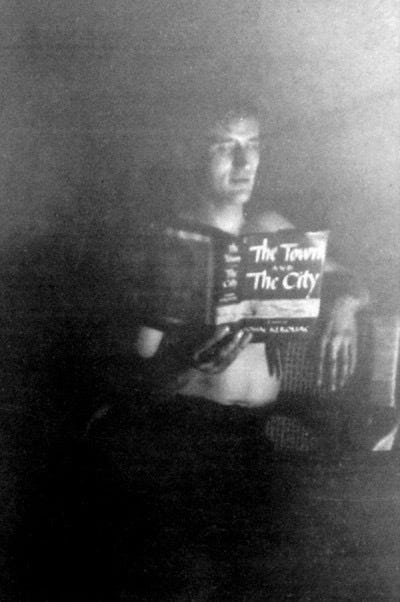

Jack Kerouac‘s first novel, The Town and the City (Harcourt Brace, 1950) was published to mixed reviews. He kept swimming in the words and the brain jazz, moving on to a new novel. He was still struggling, not only with his visions of Denver but assembling Jackson Pollack splattered inspiration into words when he hit upon an idea of how to keep the writing flowing uninterrupted. Kerouac purchased several 16-foot rolls of Japanese drawing paper to feed into his typewriter.

Three weeks and rivers of coffee later his beat odyssey was complete. Even after the continuous volleys of jive, sweat, and tears were rewound onto the rolls, it would be six long years before a publisher took a chance with On the Road (Viking Press, 1957).

Kerouac nearly drowned in the ensuing flood of publicity that brought the counterculture front and center into the staid Eisenhower years. A new underground emphasized poetry and tea over cocktails and television. Still it came preloaded with paradoxes. How could Kerouac have been so far ahead of his time with something he had written so long ago? Would he ever be able to recapture the zest he had managed to bottle so long before?

For her part, the city of Denver got an unexpected makeover as a spiritual but hip mental destination for a season of readers who were ready to check out and engage all at once. A call for a liberated joy ride with Jack and Neal and a crew of beat demons heading for Colorado? A cultural road trip was on! The men and women in their gray flannel suits had nominated Kerouac as their founding way-out downbeat guru.

“At lilac evening I walked with every muscle aching among the lights at 27th and Welton in the Denver colored section wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night… I wished I were a Denver Mexican… anything but what I was so drearily, a “white man” disillusioned… It was the Denver night; all I did was die.”

The West would figure in other Kerouac works as well. In his biography of Cassady, Visions of Cody was written in the heat of On the Road in 1951 and 52. It remained in fragments and unpublished in its entirety until 1972. In Visions, Neal became Cody Pomeroy, yet another version of the eternal Denver seeker.

“The appearance of Cody Pomeroy on the pool room scene in Denver at a very early age was the lonely appearance of a boy on a stage which had been trampled smooth in a number of crowded decades. Curtis Street and also downtown; a scene that had been graced by the presence of champions, the Pensacola Kid, Willy Hoppe, Bat Masterson repassing through town when he was a referee, Babe Ruth bending to the side-pocket shot on an October night in 1927, Old Bull balloon who always tore greens and paid up, great newspapermen traveling from New York to San Francisco, even Jelly Roll Morton was known to have played pool in the Denver parlors for a living; and Theodore Dreiser for all we know upending an elbow in the cigar smoke, but whether it was restaurateur kings in private billiard rooms of clubs or roustabouts with brown arms just in from the fall Dakota harvest shooting rotation for a nickel in Little Pete’s, it was in any case the great serious American pool hall night.”

Advanced alcoholism would claim Kerouac in 1969. In his later years, he found his way back to Denver many times, a prodigal beat king in search of the lost kingdom where he had unlocked his first magic. Where he had awakened a personal jolt and call of the articulated wild that he could feel and bring alive at 3:00 AM on a battered Royal typewriter. Or the kind he could yell out the windows of stolen cars in the near canyons.

He brought his mother out to Colorado, with the hopes of relocating permanently. She seemed enthusiastic at first, but never understood the attraction that had engaged her son for so long. The family move never materialized..

As for “the wizard of Ozone Park” as friends called him, he would always be going to Denver. He would be the outsider, the visitor, the observer, the reminder to the locals of the paradise they had accidentally created and thrived in.

Jack Kerouac’s relationship with Denver remained platonic and idealistic, a beat love story between a lost dreamer and his city in the clouds.

Cool Further Reading:

On the Road preview from Google Books

Also see:

Drive He Wrote by Louis Menand, The New Yorker, Oct 1, 2007