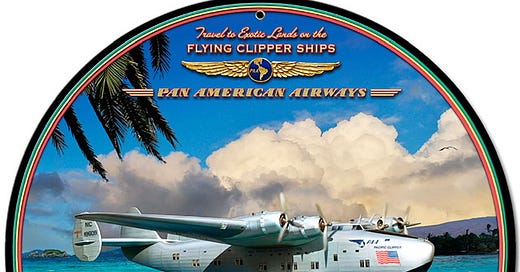

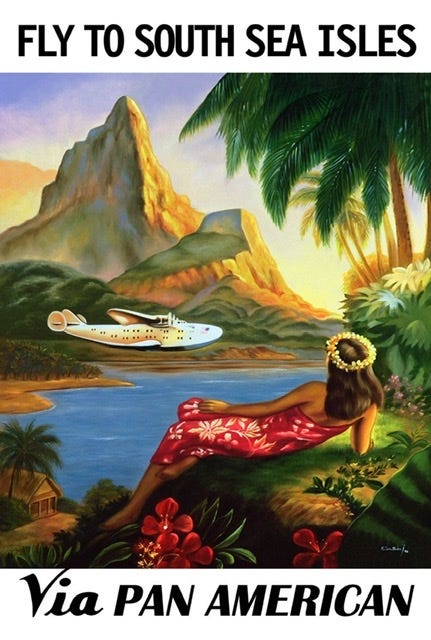

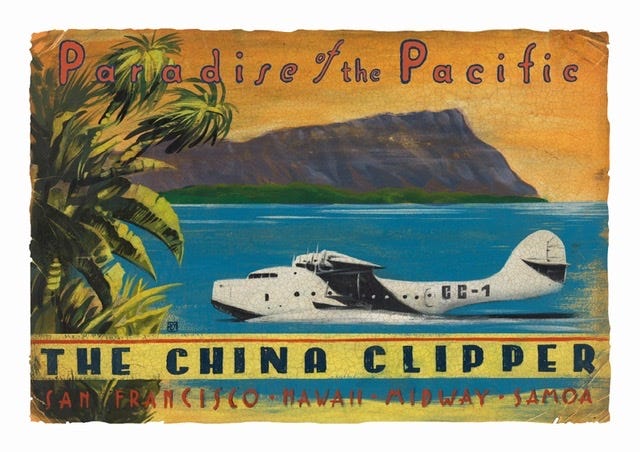

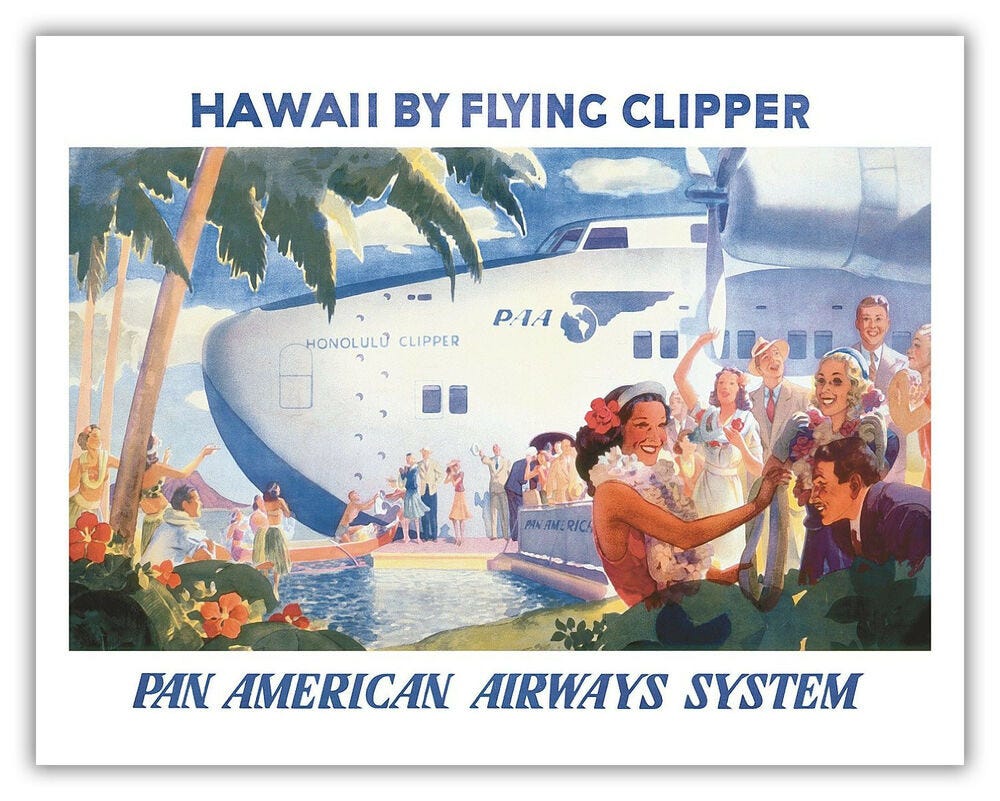

Instantly recognized by their astonishing wingspans and vast bellies, they are the essential ingredients of splashy pre-war travel posters. More than ripened sunsets, more than deco palms and sun-kissed beaches, more than fantasy island princesses splashing in blue waters, they dominate the vacation paradise art. They promise possibilities as well as a future here today. They are the colossal-but-sleek Pan American Clippers, off the drawing boards and high into the air above island, jungle, and the imagination.

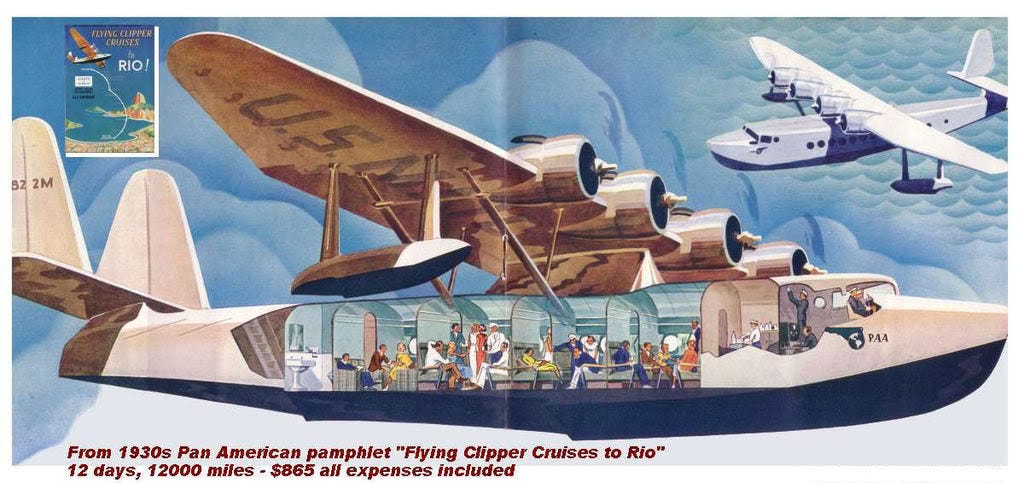

For would-be Depression era adventurers who hadn’t been flattened by the economic crisis, the ultra-modern flying arks offered distant ports for a price. Sure, the escape-driven Thirties could be altered temporarily by the written or filmed exploits of khaki-clad machos like Frank Buck, Lowell Thomas, and Ernest Hemingway. But a flight to regions with no landing strips could change your surroundings in a matter of hours.

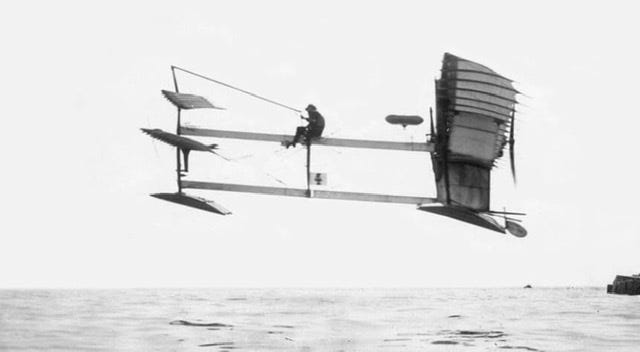

The flying boat idea was nothing new. As early as 1910, aviator Henri Fabre had navigated the Gulf of Fos in a contraption that resembled a box kite nailed to a catamaran. Two decades later, there was a high end clientele that wanted to experience the next level. Still it wasn’t the romance of far off places or the lure of landing on water that birthed the great amphibians. It was good old American commerce.

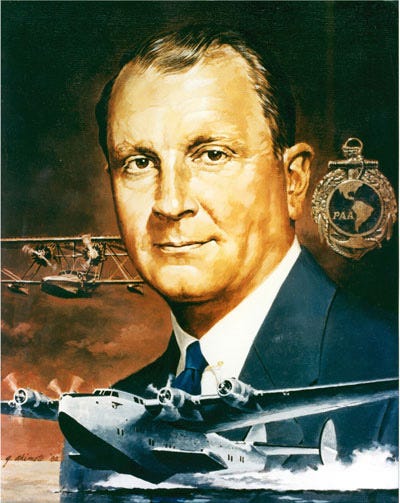

At 28, Juan Terry Trippe had launched Pan American Airways in 1927. Savvy at business and engineering, he quickly snared lucrative government contracts to fly mail to Cuba and most of the Caribbean, Central, and South America.

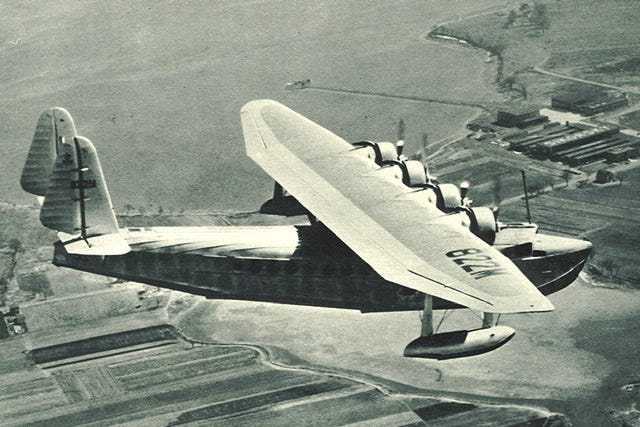

The first of the planes to bear the name “Clipper,” a term Trippe borrowed from the 19th century tall ships, was a Sikorsky S-40. Igor Sikorsky, who had fled Russia during the Bolshevik revolution, believed his 24,748-pound flying boat with the 114-foot wingspan was “a thing of beauty.”

Trippe’s technical advisor and company spokesman was the Lone Eagle turned corporate lion. Charles Lindbergh dubbed the new wonder plane a “flying forest” because of the maze of struts and bracing wires. Raring to soar, the world’s most famous pilot took 32 passengers up in the American Clipper on her inaugural flight, November 19, 1931.

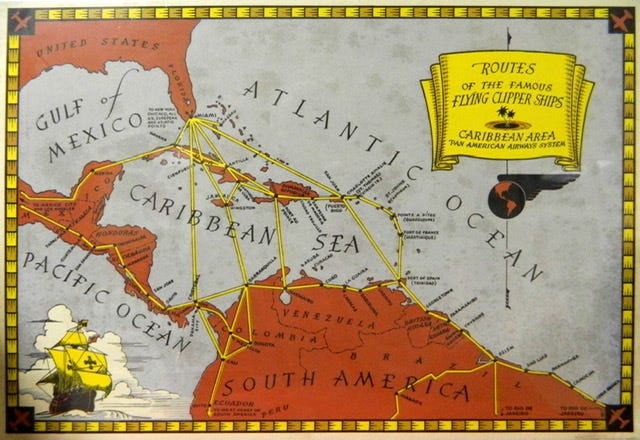

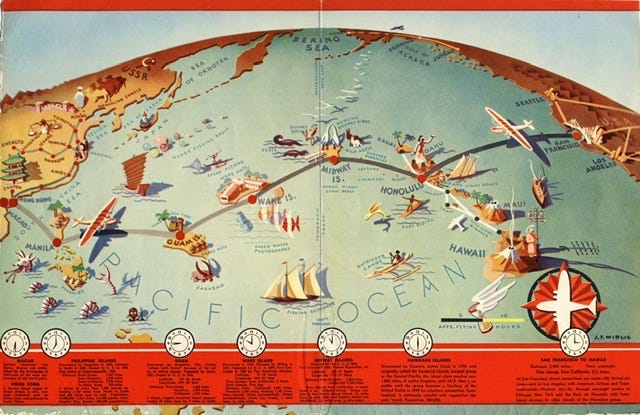

Soon, Pan American air routes covered 20,308 miles in twenty countries. Next, Trippe eyed the vast Pacific. Placing a string on Trippe’s office globe, Lindbergh pointed out the shortest route to China. America’s Columbus of the air even explored this northern route over Alaska with his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, in a single-engine Lockheed Sirius floatplane. When the Soviets nixed the idea of flyovers, Trippe looked to the tiny islands of the Pacific as stepping stones.

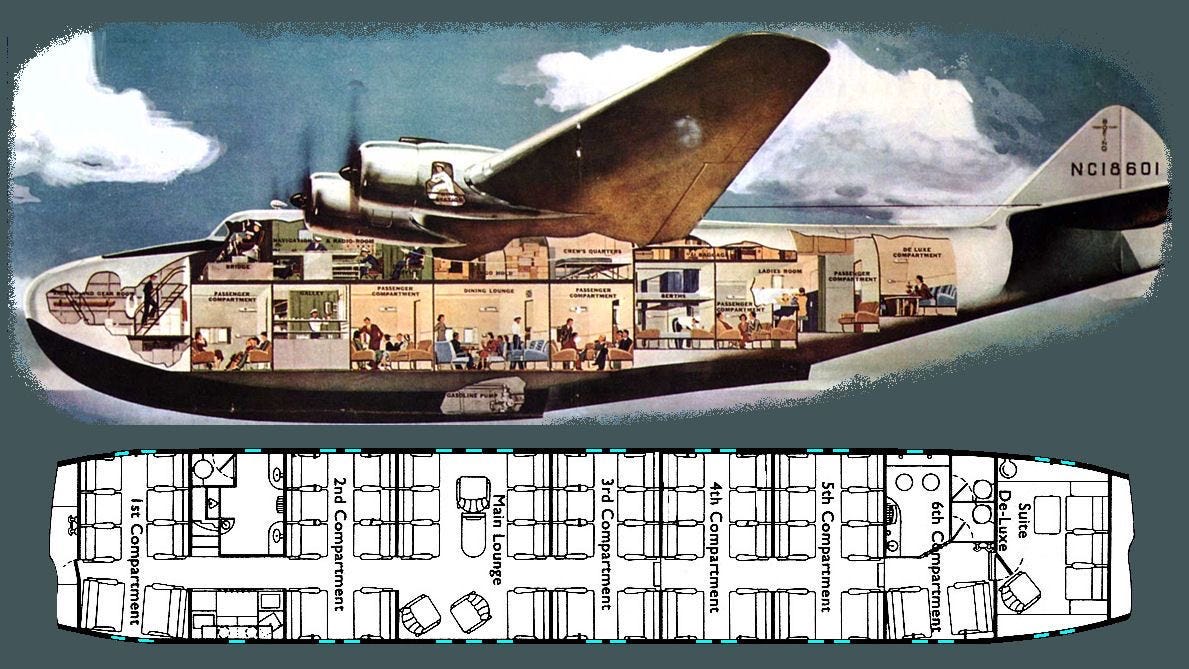

To accommodate the plan, Sikorsky designed a larger S-42 that could carry mail and 32 passengers 1,200 miles. By reducing the load to 800 pounds, the $240,000 plane could reach the 3,000-mile mark without a refuel. Sky pioneer Glenn Martin, who founded his first aircraft company way back in 1912, proposed an M-130 with a wingspan of 130 feet, a gross weight of just over 26 tons, and a flying range of 3,200 miles. It’s cruising speed was a steady 163 mph. Among his plane’s unique features was the Hamilton pitch propeller, which could be controlled in flight to maximize lifting power or conserve fuel.

The Martin Ocean Transport, powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-1830 air-cooled radial engines, was pricier ($417,201 1931 dollars, just over $7.3 million in 2021). Plus it would take a year longer to build. Trippe ordered three Martins and ten of the S-42s from Sikorsky.

Eerily, the route provided a preview of history-making World War II battles to come. From San Francisco, a Clipper would fly 2,410 miles to Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor. The next stop came after a 1,380-mile jog to the northwest to Midway, followed by a 1,280-mile hop across the International Date Line southwest to Wake Island. Guam was the next destination, 1,300-miles to the west. One final takeoff, and the last leg covered 1,300 miles to Manila Bay.

Construction would begin on fuelling stations and hotels where there had never been any, on each of the tiny connecting spots. In March of 1935, the S. S. North Haven departed San Francisco with a heavy cargo: two complete villages, five air bases, over 250,000 gallons of fuel, 44 technicians, a 74-man construction crew, a multi-month food supply, and over a million different items of equipment.

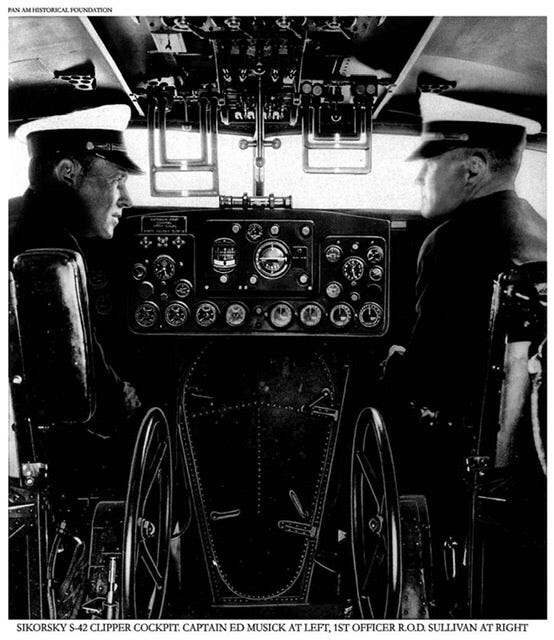

Upon testing the S-42, Lindbergh called for more fuel tanks for the Hawaii flights. Those first planes, including the Brazilian Clipper, the Jamaica Clipper, and the Bermuda Clipper, were put into Latin American service. Next, Chief Pilot for Pan Am Capt. Edwin C. Musick began surveying Pacific routes in the modified S-42 dubbed the Pan American Clipper.

The Martins arrived in October, 1935. The first, the gleaming China Clipper was tested in a Miami-Puerto Rico round trip. The timing was perfect, as Pan Am received the transpacific contract to deliver airmail at a $2 per mile rate. On Nov 22, 1935, a crowd of 25,000 gathered in San Francisco to see the China Clipper inaugurate the Pacific run to Manila. On board was a payload of 1,897 pounds, including supplies for the Pacific stops, 110,000 letters and a crew of seven including Musick.

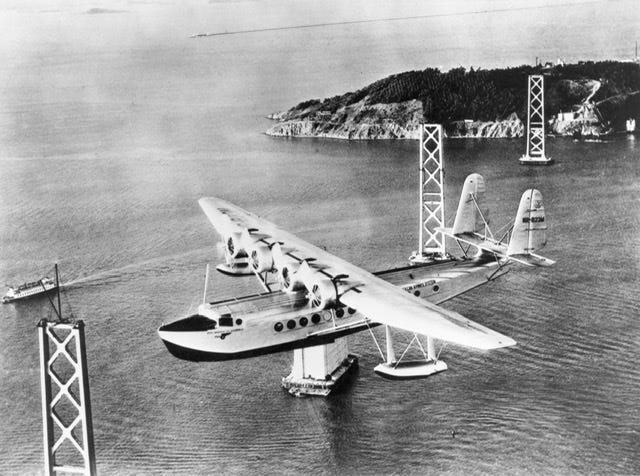

The magic of radio connected the world to the event, complete with political speeches and a bag-by-bag description of the mail being loaded. Finally, four 830-hp engines echoed across the bay. The captain made wide circles in the water to warm the engines for the 3:46 p.m. takeoff. The flight’s closest call came then and there, when Musick realized he didn’t have enough lift to clear the Golden Gate Bridge, currently under construction. Second Engineering Officer Victor Wright recalled, “...he nosed the Clipper down at the last moment and went under the bridge cables, threading his way through the construction wires. We all ducked and held our breaths until we were in the clear.”

But in the clear they were, climbing to an altitude of 7,000 feet. Twenty-one hours and four minutes later they landed in Hawaii, seen clearly from 10,000 feet because of the erupting volcano Mokuaweoweo. Worldwide radio covered each of the succeeding takeoffs and landings until, 59 hours and 48 minutes after launch, the China Clipper skimmed the waters of Manila Bay. It was 3:32 p.m., November 29, 1935.

Public imagination went full throttle. In 1936, the silver plane hit the silver screen, with Pat O’Brien starring in China Clipper. The fare to fly one-way from San Francisco to Manila was steep, $799 (the equivalent of a $15,473.87 e-ticket today), but there were many customers ready to occupy the spacious passenger cabins.

The first tragedy for the great planes claimed the line’s biggest star. On Jan. 11, 1938, less than three years after his electrifying flight to Manila, Capt. Musick was taking off from Pago Pago in the Samoan Clipper when he reported an oil leak in engine number 4. In an attempt to lighten the plane’s weight for a safe landing he opted to dump fuel. Vapors collected in the structure of the wing, causing the Samoan to explode in a mid-air ball of fire.

After Martin delivered the Hawaiian and Philippine Clippers, Boeing introduced the B-314s, deluxe twin-decked flying hotels weighing 41 tons when loaded to capacity. The company produced a dozen of these largest passenger planes of the day from 1939-41. Among them were the Honolulu, Yankee, and California clippers.

The Pacific excursion era shut down completely when the tropical paradise destinations erupted into war zones. The Philippine Clipper was en route to Guam when ordered to return to Midway on the morning of Dec 7, 1941. Upon landing it was strafed by 96 Japanese machine gun bullets. Still, they made it back to California. Not so lucky was the Hong Kong Clipper II, having been in service just seven weeks when it was destroyed in an attack on Hong Kong harbor on Monday, Dec 8.

Pan American was thrust into wartime action, as were her Clippers. Converted to cargo planes, they carried over 3 million pounds in 1,219 Atlantic crossings in 1942 alone. The company itself logged 90 million miles in 18,000 wartime ocean crossings. Most of their service was classified and never recognized publicly.

President Franklin Roosevelt celebrated his 61st birthday on Jan 30, 1943, aboard the Dixie Clipper as it returned from a secret summit at Casablanca. The China Clipper carried uranium ore for the Manhattan Project, where the first atomic bombs was constructed.

The war changed the carefree era the clippers represented. Those times could never be recaptured. The curtain came down abruptly on Jan 8, 1945. The China Clipper, having logged over 3 million miles in ten years, crashed in a night landing at Port of Spain, Trinidad.

The Clippers represent an exciting and over-the-top time in the history of flight. No longer were distant destinations the exclusive domain of the professional adventurer. For a price, anyone could go anywhere anytime, flying through the air and landing on the water, and do it in style. In their time, the 28 Pan American Clippers changed the public’s idea of global air travel in a big way. The possibilities for what might come next were as vast as the Pacific horizon.

Magnificent photo's