On December 21, 1858, a group of miners at the Cherry Creek diggings came across a calendar and got the shock of their lives: there were only four shopping days left until Christmas. Unseasonably warm temperatures and an insatiable lust for riches had almost overshadowed the holiday completely. With typical frontier spirit they planned a celebration out on the edge of nowhere, just west of present Aurora, Colorado. Little did they know that even Santa Claus was coming to town

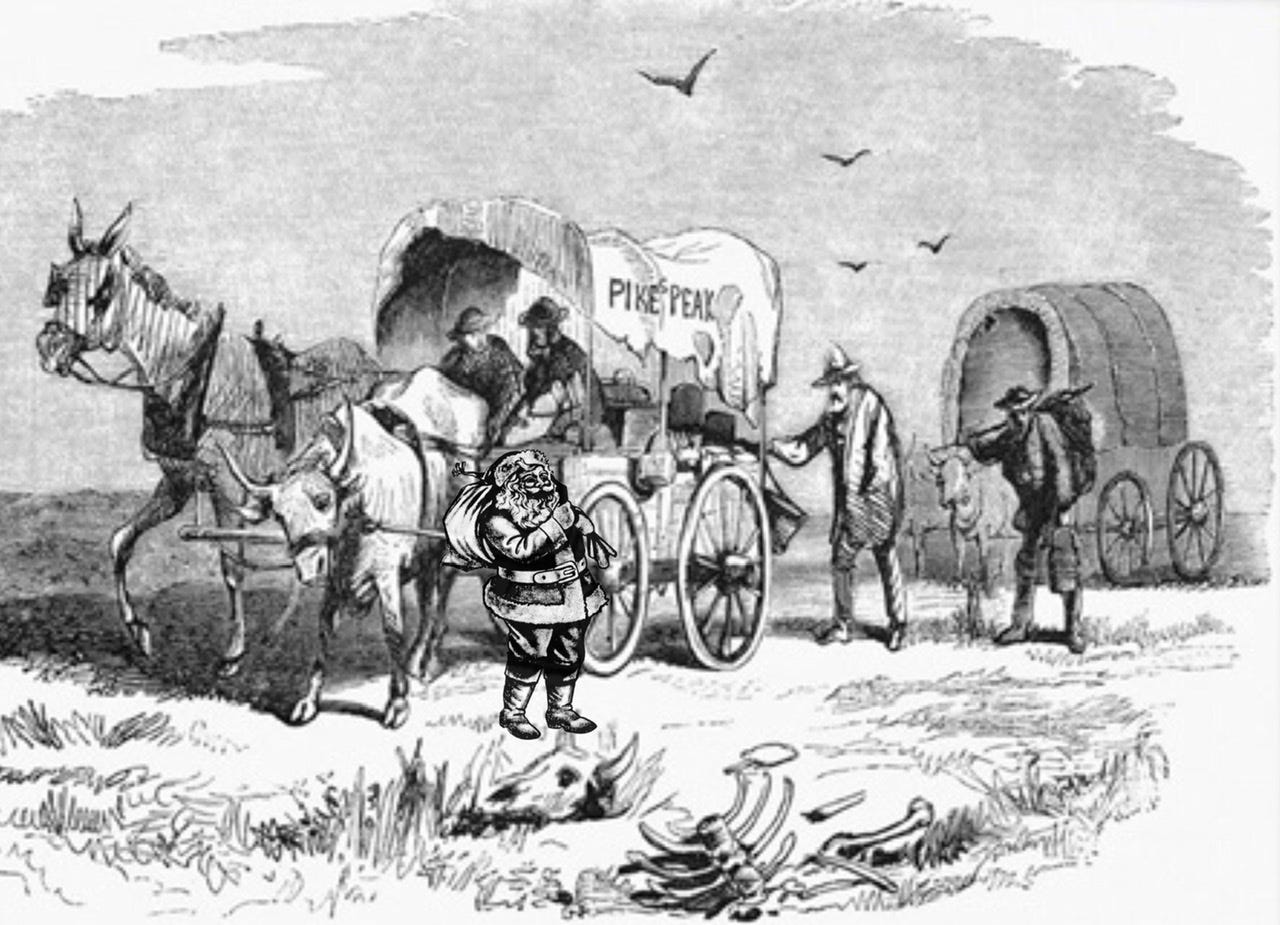

And it came to pass in those days that wise men and foolish alike rushed out west searching not for frankincense and myrrh but for gold. They followed no star just a slogan that said “Pikes Peak or Bust.” Most would do the latter.

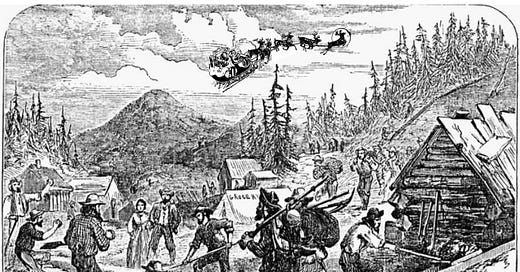

They set up their tents and shacks on either side of Cherry Creek and begin panning for the shiny dust. Two town sites were incorporated in the autumn of 1858. Auraria on the west was mostly transplanted Georgians. On the east, Denver City was made up of Kansans who had come with Gen. William Larimer. When Capt. R. A. Spooner‘s party from Nebraska and Iowa arrived on November 4, the region was already being called the “New El Dorado.” By Christmas though, no one had struck it rich. Now the talk concerned waiting for the spring thaw and getting to the mountains. There, they would surely find the yellow ore.

In the meantime, someone in the Spooner camp had discovered the calendar and just for kicks decided to see what day it was. Immediate holiday depression set in. Here they were, 600 miles from a railroad and 200 miles from the nearest post office at Ft. Laramie, Wyoming. (Enterprising trader Jim Sanders became the Denver postal service on November 23 agreeing to carry letters to Wyoming for $.50 per piece. He would bring the return mail, Christmas cards and all, on January 8.)

There were some two hundred men, five women (four of them married), and perhaps a half-dozen children in this 60-day old metropolis. All were sure they were not included on Santa’s map. Why, who had ever heard of such a map with names like Larimer, Curtis, Stout, and Wynkoop?

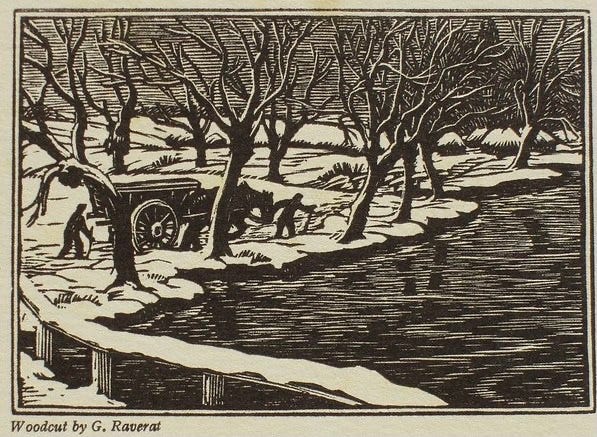

As the Denver doldrums cast a pallor over the yule season, a jolly old elf slowly made his way toward the enchantment. Riches Wootton and his wife were driving two ox carts from what seemed as far away as the North Pole—Fort Union New Mexico. A merchant by trade, he hoped to be a peddler just opening his pack in the new city. In the back of one wagon he knew he was carrying the hot item for the Christmas of 1858, resting comfortably next to his two sleeping children. If the weather held and the creek didn’t rise he just might make town by, say, December 25.

Back in Denver the mood had improved. French Count Henri Murat was making arrangements to host an open log cabin. His German bride Katerina baked cookies and molded candles for a tree that was being imported from the foothills.

In the Spooner camp, as glowingly reported by correspondent A. O. McGrew to the Omaha Times, a pioneer Christmas dinner with all the trimmings filled the air with heavenly scents. Three cooks named Sullivan, Crum, and Frary were putting together an impressive menu of buffalo, ham, venison, elk tongue, bear meat, rabbit, wild turkey, squirrel, quail, baked potatoes, beans, rice, and biscuits. Their gourmet dessert tray would include dried mountain plums, apple and peach pie and rice pudding. (In such spare times one must wonder if this array was cooked up in the Spooner kitchen or in the brain of McGrew, but suffice to say a celebration was in the offing.)

Christmas morning was recorded as “soft and genial as a May Day, as beautiful as ever shone. Not a breeze whispered through the leafless cottonwoods.” It was calm and one could easily hear the sound of wagon wheels and the prancing and pawing of each oxen hoof. According to Henry Edward Warner in a 1900 Denver Times, “The sun had just rubbed it sleepy eyes and peeped in on the little settlement … when Santa Claus made his appearance.”

Wootton unloaded his goods and set up his tent. That task completed, he rolled out a barrel from one of the wagons and cracked the top with an axe. Inside was Taos Lightning, a potent moonshine guaranteed to start an electrical storm in the head. It was the first whiskey in the diggings. Said Warner, “it went down like a swain on his knees to the object of his affections. It hit the stomach all in a lump and sent cheerful feeling up to the roots of the fellow’s hair and back again to his toes in one howling, rip roaring succession of luxurious vibratory spasms of exquisite joy. It beat grand opera without even trying.”

“Uncle Dick gave the whole town a free blowout,” said witness A. E. Pierce. Everyone helped himself freely, using tin cups.” Larimer’s son, 18-year-old William, said “several did help themselves, and so often that they needed help to reach their cabins.” According to the General,Methodist Reverend George W. Fisher’s plans for a religious service were dashed: “Some were in favor, some were lukewarm and some opposed entirely to the program. This opposition grew when that arch opponent of religion, whiskey, was introduced.

There would be no football games. A wrestling match for two yoke of oxen and a wagon was quickly arranged.

A bonfire and hoedown began in the streets. Men locked arms and danced to the songs like “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and a new tune composed by McGrew called “Root, Hog, or Die.”

“Active feet went into motion,” he wrote, “and in the weird light we danced until midnight. Groups of Indians with their squaws and papooses filled the shadowy background. It was a picture that Rembrandt would have loved.” Meanwhile, at the Murat cabin, guests including Mrs. Wootton and her children decorated the Christmas tree and sang “Silent Night.”

As for the most popular man in town, he was call “Uncle Dick” from that day on, given a full share in the Auraria Town Company, and land on which he would build his business. He made sure none of the celebrators drove home that night— many settled down for a long winter’s nap on the banks of Cherry Creek.

What we know about that first Denver Christmas of 1858 has been obscured by visions of sugarplums over the years. We can bet our stockings that Colorado’s first bash was a beaut. In dignity and stupor, the pioneers held they’re tin cups high to a future bright with promise in the transitory time that vanished quickly, like the ghost of a Christmas past.

***

This story appeared as “They Held Their Tin Cups High” in the anthology Colorado Christmas, edited by Sara Lohaus and Jan White, Partridge Press, ©️1990.

That was a great story Mike. I enjoyed reading it. Thanks!