There’s something about Mary. Mary Coyle Chase. Ace Colorado reporter whose dream was to write plays. That something turned out to be an invisible rabbit, 6’ 1 ½” tall (a half inch taller than Barack Obama) who could only be seen by two people. One was the hero of her play, Elwood P. Dowd, who would gladly present anyone with his card and invite them to have a drink with his fuzzy best friend. The other was Mary herself, who invented Elwood as well as Harvey.

The curtain was grinding downward on World War II. Back in 1944 Denver, anxious families awaited news of their loved ones still in harm’s way. For one resident, there was no hope or anticipation. Well aware of the woman’s backstory, Mary Chase watched her most weekdays as she dragged herself to and from a nearby bus stop. She was a widow. Her only son had died in combat in the Pacific.

By age 36, Chase had become a stay-at-home mother, raising three sons while her husband worked at the Rocky Mountain News, where years before they had kindled an office romance. Her hobby, her passion, her dreams, had always culminated in a loose goal to write for the theater. Somewhere along the line, this shattered woman Chase watched going through the motions of life had become an unlikely symbol for her target audience.

Writers search for answers. For Mary Chase, the question was blunt. Could she write a play that would make a war-weary public laugh? For this she would need to dig deep for some upper level silly, which she did in the form of a transparent rabbit and his mild mannered, ever-buzzed companion.

Mary Coyle was the fourth and last child born to Irish immigrants and Denverites Frank and Mary McDonough Coyle, on February 25, 1906. The family, which included four Irish uncles on her mother’s side, loved to thrill her with Irish folk tales of banshees, leprechauns, and the shape shifting pooka. The pooka could take any form, a horse or a goblin, a goat, a dog, or even...a rabbit. Worse, it could talk and mimic humans, giving it all the tools necessary to confuse and fluster.

At age eleven, Mary attended a production of Macbeth at the old Denham Theater and was absorbed by the words and the action. Academically, she graduated from West High School at sixteen and went on to attend the University of Colorado and the University of Denver.

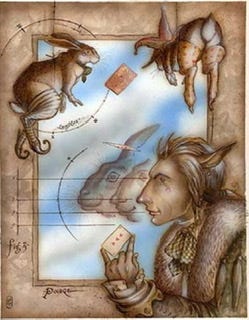

Employed by the Rocky in 1924, Miss Coyle relished the action, the writing, and a series of stunts. Once, she debunked the superstition that disaster would befall any woman who entered a mine or excavation site. Disguised in man clothes, she boldly ventured into the incomplete Moffat Tunnel and emerged unscathed.

For another feature, she took truth serum and managed to lie. When no photo could be found for a sensational divorce scoop involving a local tennis enthusiast, Coyle boldly ran into the Denver Country Club, grabbed a team picture from the wall and scurried out the door. Once outside, she hailed a passing coal truck to get her downtown. By the time club officials could figure out what happened and follow her to the newspaper, she had already had the photo copied and was able to present them with the original.

In 1929, three years after her marriage to reporter Robert Chase, she was fired over a practical joke. The News had distributed some charity baskets for Christmas. Mary phoned the city editor and blasted him big time in a sharp brogue, complaining bitterly about “wormy apples.” She was reinstated, but soon left, by choice, to freelance and raise Michael, Colin, and Jerry.

By 1934, she was writing plays. Her first, Now You’ve Done It, flopped on Broadway in 1937. A second was never produced. Her third, Sorority House, culled from her Boulder days, was sold to Hollywood for $2,500.

In 1942, she was working on her riddle that had begun with the woman at the bus stop, then multiplied toward so many who had lost so much. In later interviews she said she had tossed ideas around and out for three months, until one morning she awoke from a strange dream in which she had seen a psychiatrist pursued by a great white rabbit. She recalled tales of the pooka. Fueled by cigarettes and coffee, Mary Chase dropped into a creative trance that lasted nearly two years. By D-Day, June 6,1944, The White Rabbit was complete.

She mailed her manuscript to producer Brock Pemberton in New York, who had overseen her work seven years previously. A few nights later, while Mary was reading a bedtime story to her boys, Pemberton called, wild with praise. He promised a production to be directed by living legend and former Denverite Antoinette Perry in what would cap her monumental career.

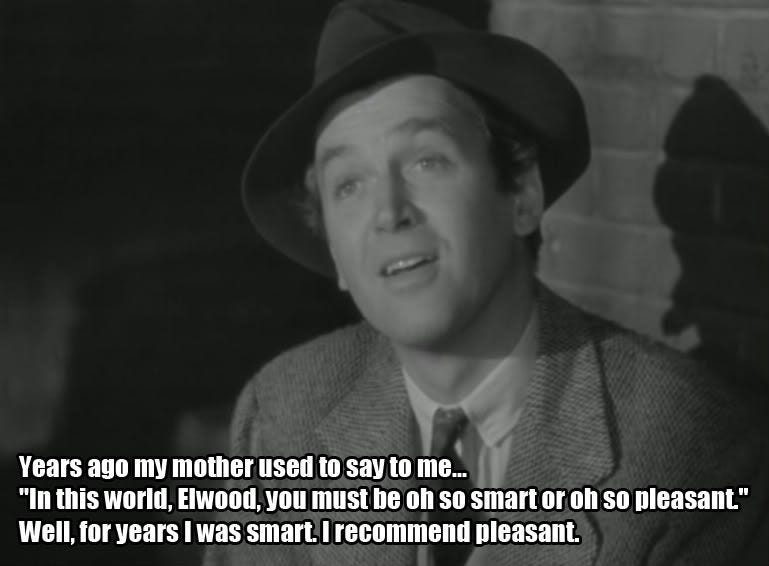

Comedian Frank Fay, who himself was rebounding from a bout with the bottle and a disastrous marriage to Barbara Stanwyck, was cast in the lead. He would play the likable lush from “a town in the West,” Elwood P. Dowd, who meets his bunny buddy underneath a lamp post on Fairfax. (Denverites would swear it was based on Colfax.) Fay was a talented guy, but was he lacking the sweetness Mary had installed in Elwood? After her star referred to her as a “dumb Denver housewife,” she must have wondered.

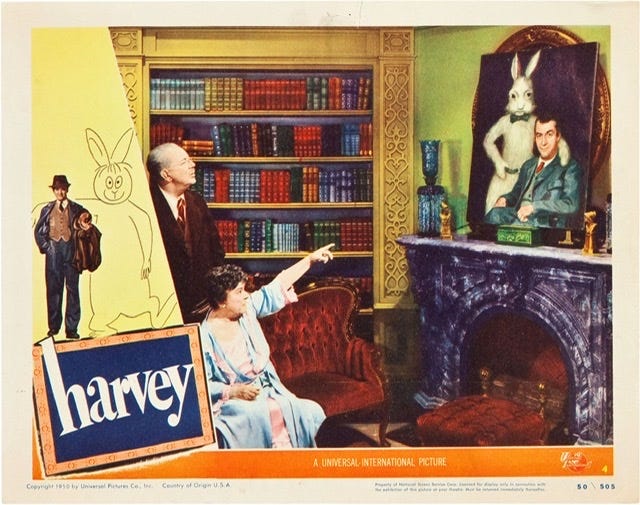

Her nerves were on slow boil for the Boston opening. The dilemma of having Harvey remain imaginary, or dropping in an actor in a $650 rented rabbit suit had kept her up nights. An opening night note of encouragement from her husband did exactly the opposite: “Don’t be unhappy if the play does not succeed. You still have your husband and your three boys, and they all love you.”

She was so well prepared for failure that success seemed as real as her silly rabbit.

Copies of the Boston Record hit the newsstands just before dawn. Said Leo Gaffney,‘This is a play with a spiritual message in farce terms.” With that, the big white rabbit was ready for the Great White Way.

Robert and Mary Chase borrowed $300 to attend the Broadway opening at the Forty-eighth Street Theater on November 1, 1944. The tension broke minutes after the curtain rose. Harvey was a sensational onslaught of unexpected heart and humanity. People were going wild over an imaginary rabbit befriended by a drunk. The critics’ only complaint was of aching ribs from too much laughter.

“If a rabbit, six feet one and one-half inches tall, sits down beside you at Charlie's, that will be Harvey. And you may count yourself fortunate that Harvey appears to those who are happy, and to those who have taken a drink now and then through the years and are the better for it. If Harvey does not visit Charlie's he can be found at the Forty-eighth Street Theatre, where Mary Chase's new play opened last evening with "Harvey" in quotation marks and giving a very delightful evening to the theatre. Brock Pemberton, who hitherto has held sternly apart from plays about rabbits, is the producer and Frank Fay and Josephine Hull are providing the last word in acting. Harvey, in or out of quotation, is one of the treats of the fall theatre.”

--Lewis Nichols, The New York Times

Nov 2, 1944

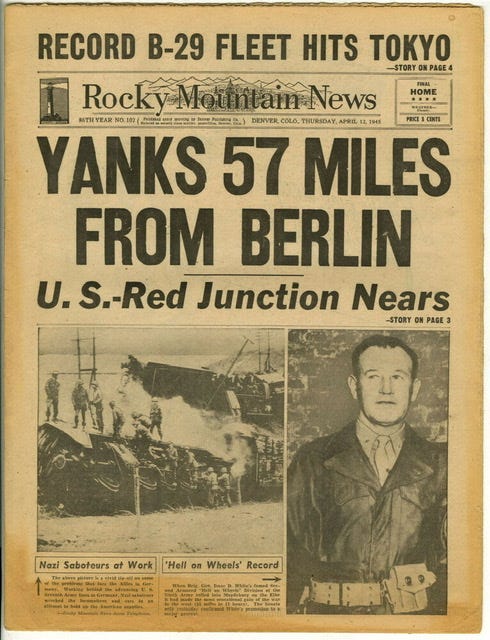

The Pulitzer Prize winners, announced May 7, 1945, paint the landscape of the time. War correspondent Hal Boyle won for the Associated Press. Sgt. Bill Mauldin won the editorial cartooning award. Novelist John Hersey’s war story A Bell for Adano (Knopf), took the fiction award, and to no one’s surprise, Joe Rosenthal snared the photography award for his picture of the flag raising on Iwo Jima. For Music, it was Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring.

And for the drama award, although Tennessee Wiilliams had lots of support for the fragile animals of The Glass Menagerie, the prize went to Mary Chase and the indomitable Harvey. The next morning, Germany surrendered and the war in Europe was over.

Harvey’s Broadway run was 1,700 performances over the next four and a half years. The passing of director Antoinette Perry, for whom the Tony Awards are named, at 58 in the summer of 1946 was the show’s only low point. Harvey became one of the most popular comedies of all time.

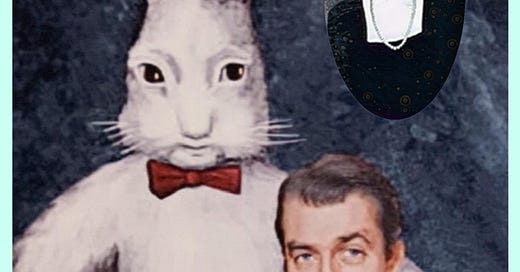

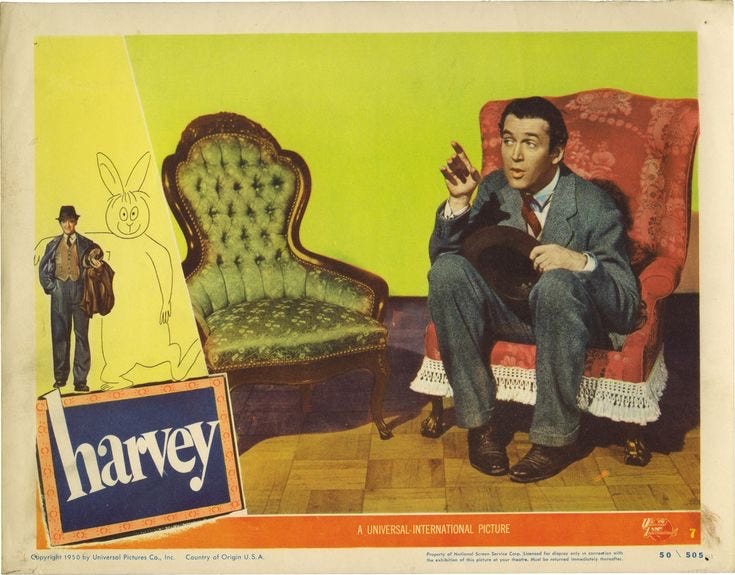

Numerous studios bid for the screen rights. Universal won with the first million-dollar bid in history. The film version, with a screenplay collaboration by Chase and Oscar Brodney, released in 1950, earned Jimmy Steward an Oscar nomination. Josephine Hull won the Best Actress in a Supporting Role Oscar for her performance as Elwood’s beleaguered sister Veta. Chase kept her word and never let her creation become a television sitcom.

Back in Denver, the sudden fame put Chase in a bittersweet fishbowl, even though her hometown newspapers still referred to her as “Mrs. Robert Chase” and printed her home address. Once she awoke from a nap to find three strangers standing over her, just watching her sleep.

“Most people believe...that in this world there is a magic room, papered with money, lit with fame, resounding with the sweetest music of all, piped from heaven like Muzak; that in this room is the life glorious and no pain. They wonder how you got in there while they’re kept out. Most people believe this as a fact and yet call a six-foot white rabbit a pure fantasy.”

--Mary Chase, McCalls Magazine, (1952)

Though her life was never the same, Chase did manage to keep her sanity. She wrote fourteen plays, three screenplays, and two award-winning children’s books, Among her works are the mildly successful Mrs. McThing, starring Helen Hayes, and an exploration of the world of teenage boys in Bernadine, which became a movie in 1957.

But it was her home run, her perfect game, her play that charmed survivors of World War II young and old, her giant wise rabbit that went down as easy as an afternoon cocktail with Elwood P. Dowd, that gave her a unique place in the history of American theatre. She had made a sad world laugh.

The woman Dorothy Parker called “the greatest unacclaimed wit in America,” died of a heart attack at 75 at her Denver home on October 20, 1981. Though Harvey was imaginary, his effect on Mary Chase and the rest of us was very real.

Great story. I remember Harvey. Oh, I remember Jimmy Stewart too. LOL**